Our CEO Interview with the Future of Protein Summit Organiser Nick Bradley

Full Interview here

A seasoned protein chemist and serial entrepreneur, Dr Seronei Chelulei Cheison has invaluable experience in the pet food industry where he worked for MARS Petcare and led projects in alternative protein innovation and palatant development

Thank you for joining us Seronei – and for all of your help with the Summit and Protein Production Technology International magazine. It would be nice to get to know you a bit better. Could you tell us about your pathway into the industry?

Sure, my entry into alternative proteins started at MARS Inc’s Global Petcare within what was then GAST (Global Applied Science & Technology). At MARS, I was responsible for leading protein innovations to build alternatives to functional animal proteins that the business was heavily reliant on to deliver functionality for wet pet food. During that stint, I got exposed to proteins from plants and biomass like algae, novel proteins as those developed from sugar beet leaves (Rubisco), etc.

Later, I had contacts with colleagues and peers working with insect proteins and the HORIZON2020-funded project aimed at extraction and valorization of proteins from salad, olives, tomato, and rapeseeds. When I left MARS to start my own business, Sinonin Biotech, it became clear that the pet food space, especially, needed more than plant proteins for sustainability because of the absolute mismatch between the growing demand vs growth of protein sources. That is when we heard countless repetitions of the threat of imminent protein deficiency because of the ballooning human population, etc, etc.

Currently, I work with customers that are looking for sustainable plant, insect, proteins from mycelium, single-cell proteins like those from specific bacteria, and other alternative sources. It is increasingly clear that the first casualties of a protein shortage would be our four-legged friends and family member(s). Achieving protein supply sustainability means there is a need to look beyond traditional protein sources.

I started off as a Dairy Science & Technology BSc at Kenya’s Egerton University (named after Lord Egerton of Taton, UK). Then went to my academic 40-days-in-the-desert, China. I spent about four and a half years away from my young family but came up tops in my MSc and PhD classes graduating Summa cum Laude in both. That opened the door to the TU Munich, facilitated by one of my academic ‘fathers’, Uli Kulozik. In China and Munich, I majored in enzyme hydrolysis of proteins from milk, feeding the frenzy of ‘nutraceuticals’ and ‘bioactive peptides’. This was an incredible journey into the OMICS as well because that is where I saw application of advanced analytical tools, worked with industry to address some key research questions and mentored students in Food Enzymology. At the end of my TU Munich process, I wrote a thesis and earned the German habilitation (Venia legend), the equivalent of a DSc in the UK system. Then came to MARS. The rest, as we say is a beautiful story!

You have told me in our discussions that Sinonin Biotech was founded out of the realization that there was an urgent need for players in the interface between expertise in protein technology and application in the petfood space, especially because of the pressure on protein demand’. Could you explain what you can do for clients and what your USP is?

Bringing the knowledge of protein chemistry and food enzymology on the one hand and having actively worked in the pet food industry and especially in pet food product development with alternative proteins and pet food palatability on the other was an outright winner because it set us apart from most of our competitors who possess one OR the other. From the word go, we were able to secure critical partnerships and commitments to help our business partners deal with specific needs in alternative proteins selection and test criteria as well as palatant selection strategies. That has been and remains to be our USP in this fast-paced industry.

Have your peers and colleagues in this space been enthusiastic and come to you for help in this area? What challenges have you had?

Obviously, doing business in Germany takes a lot of courage for someone who is not well versed in their language. So, the biggest challenges from the word go had to do with the legalese and dealing with the mountains of documents. We made it clear that we couldn’t sign anything unless we had read first! That is quite a challenge, even for native German speakers, as this country loves paperwork. Once we identified partners and coaches, we were able to outsource a lot of the tasks that are routine or bureaucratic so that we could focus on what we are good at. Obviously, the biggest challenge is market penetration and the need to grow the market sustainably while staying at our level on quality. As we seek to expand our reach, we realize that the space is becoming more and more complex, and the players want answers faster and reliably. So, we are very choosy on what to accept since we know how wrong it can go if we are overwhelmed or accept a task for which we don’t have competence currently.

You mentioned partnerships before. How vital are collaborations in your particular field of work?

Nobody has monopoly of knowledge. Certainly not even competitors! We need to nurture win-win collaborations and encourage strategic partnerships. We look for partnerships with raw material producers as suppliers of test materials. We also reach out to them to develop specific solutions to meet the needs of our end-user customers and we are so far grateful for the willingness to collaborate and adapt. We need collaboration beyond industry, particularly with knowledge centers and universities as well as contract labs. Although the universities work on fundamental knowledge and offer this largely for free, players like us tap into that pool and action the knowledge into specific ‘applied’ science solutions with business-relevant applications.

Presumably in emerging areas such as insect proteins, there is an an immense opportunity for collaboration?

Currently, we are faced with realities about the lack of information on insect protein techno-functionality relevant to pet food application, specific reactivities in pets (allergy for example) and the suitability of traditional protein-separation technologies for insect material processing especially because of the high lipid content. For other technologies, we see an opportunity for scaling optimization to help move the technologies from ‘concepts’ to industrially exploitable opportunities. A case in point is cell culture. That meat can be developed from cells is promising. However, meat is more than a mass of cells. Structure is important. We need collaboration to develop innovative muscle structure, be it at scaffolding or cell alignment and lipid entrapment.

On the topic of cultured meat, what did you make of developments at COP27?

I love the ‘stunts’ of the Good Meat guys, serving innovative products to power where the whole world is watching is a masterstroke in marketing genius. It is not in boardrooms or scientific conferences; it has reached the power(wo)men and this is huge. The choice of when and where to storm the headlines couldn’t have been better. The next challenge is to make the products affordable to the masses.

So, Seronei, you will be appearing on a panel at The Future of Protein Production on the topic of ‘Springboarding alternatives: How early adoption in pet food can drive commercialization’. What will be the key takeaways for our delegates from what you bring to the table?

Let me start off by saying what an honor it is to be part of that select group of discussants. Leo and Nick are captains in their fields, and pioneers in insect rearing and exploitation. Insects are sustainable, rearing is scalable and the opportunities to innovate with the four main products (proteins, lipids, chitin and frass) are endless. So, to be speaking about the potential of insects in the pet food area is huge. It helps us acknowledge that not only is the ‘protein hunger” a “human food hunger”, but it is also impacting us in a holistic manner – including the four-legged members of our family.

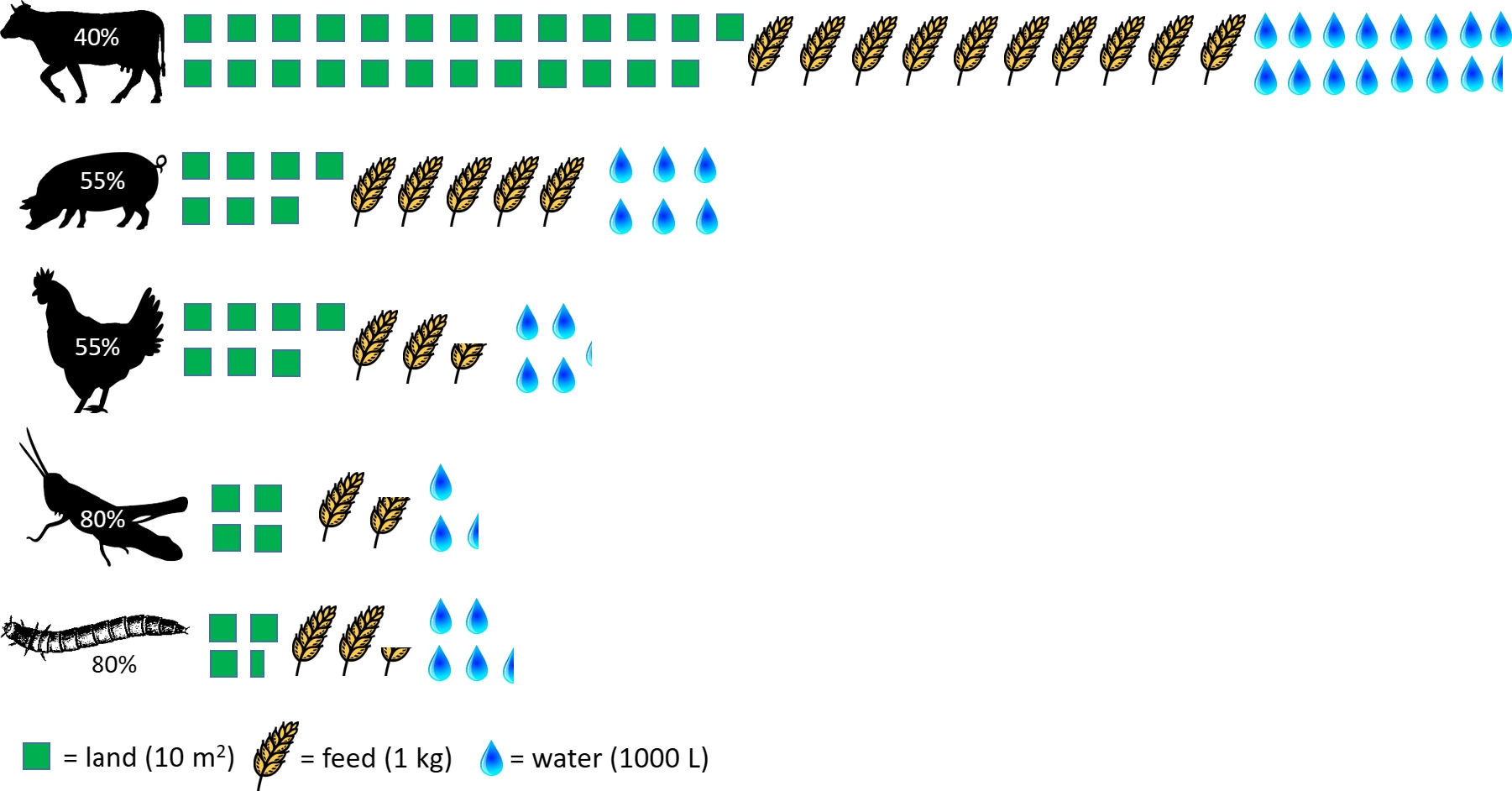

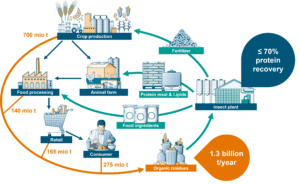

We want our delegates to appreciate that insect products help reduce the pressure on traditional proteins. Circular economy is promoted by insects, which recycle up to 70% of the protein from wastes and it’s important to say that the quality of proteins from insects is in no way inferior to traditional proteins. We also wish to emphasize that insects provide immense opportunities for innovations and research, and we encourage academia and industry to find win-win collaborations. Bugs for Bucks is real!

We need more entrepreneurship to continue improving the rearing, harvesting, and processing technology. We want us all to appreciate that with technology, we shall be able to extract the products from insects to render them more acceptable and reduce the negative reactions and disgust. I believe if anybody were served a whole beef, or pig, we would experience similar reactions. But ‘cuts’ render the meat products acceptable and widely embraced. In a similar manner, we should encourage ‘cuts’ in terms of valorization processes to eliminate or reduce the disgust.

Finally we wish everybody walked away with a simple truth: We must work together. Smart is not walking alone. Wild animals know that to survive they have to be in a ‘pack’ or ‘school’ or ‘herd’. Collaboration is not antithetic to winning. We just have to find touchpoints and clearly demarcate out our win-win strategies. Easier-said-than-done, I know. But let us keep trying.

Finally, we wish to emphasize that insects are not alien to pets. Cats shall be seen chasing flies, grasshoppers, etc, while even fish once in a while grab insects on water surfaces.

Presumably you get to taste a lot of products in the marketplace. Which ones impress you and why?

I have been meat-free now for quite a few months and in that time, I have had occasion to sample the ‘chicken’ and ‘fish’ as well as ‘vegan cheese’. They all tasted better than I had assumed and despite the chicken and fish being relatively ‘dryer’, I thought the product developers did a wonderful job to compensate for those ‘weaknesses’. I guess one potential risk I see going forward is what I call ‘extrusion fatigue’. Luckily, some disruptors like our friends from Umiami are claiming extruder-free texture technology! Can’t wait to sample their products!

How vital do you think it is for future generations that we make this shift to alternatives to meat?

In my opinion, the benefits are way more than a safer, cleaner, and responsible care for a planet. The shift into alternative protein space is shaping business and research and innovation beyond the agro-food sphere. Whereas it affirms care for a sustainable exploitation of our resources, it also spurs a mutually beneficial relationship between the innovators and auxiliary services including business managers. Some of us are good at the technology but we probably need finance gurus to run business models for us and work on fundraising pitches as well as manage the business to profitability. The future generation finds an expanded business space! It is up to them to stretch it beyond the future we shall bequeath them.

I think this next question will be quite personal for you. In the developed world, people ‘live to eat’ and can therefore afford some ‘value-added’ food, but we should not forget that there is a huge part of our global population for whom a meal a day is a miracle. How do alternative proteins fit into food security?

I grew up under ‘eat to live’ circumstances until around age 18. In Kenya, choice is not about what else food brings on as value, rather whether my stomach is filled. Because the next meal is not a guarantee. And we are not even talking a quality meal. For a part of our population, protein hunger is real. I grew up eating ‘potato soup’ as a ‘vegetable’ and we used to eat ‘ugali’ (maize meal product that is the staple food for most African populations). Imagine potato starch on maize starch for food! So, the most important ‘wellness’ for them that still find themselves in that paucity of options is sufficient proteins. That is why I think, despite making a career out of bioactive peptides and functional protein derivatives, it is nutrition first before we pressurize the supply chain to supplant pharma in that respect. Of course, I can’t stop whoever affords to from accessing that aspect of food sitting in the interphase between nutrition and pharmaceuticals. However, the nutraceutical aspect of food may be delivered more by non-protein materials such as polyphenols and food color complexes which would not necessarily impact protein supply.

We live in a big world with lots of countries, lots of regulators. Do you think we should come up with a global standard to simplify the advancement of alternative proteins?

If you mean harmonizing standards and specifications, I would say it is both good and debatable. It is always important to harmonize a couple of critical aspects: safety and regulatory aspects. This would reduce complexity and allow transversal movement of products across borders and continents. I mean, if we had a harmonized global standard for fermented proteins to define toxicological ‘watchouts’ such as heavy metals, biogenic amines and residual DNA/RNA materials, for example, it would make it easy to have a producer release a product with a standardized global specification that could be acceptable anywhere on the globe. The challenge is as we see today even in traditional proteins, there is sometimes some clear trans-Atlantic tension in terminologies and specs. Having one spec enables costs to be cut, prices drop and stabilize, and movement of commodities would be less complex and faster!

We cannot have one of these interviews without talking about scaling. Where do you see the challenges and the solutions here?

The challenges are more technology-related. For cell-cultured and ‘pharmented’ proteins, the challenges are mostly bioreactor level. For plant proteins it is related to separation technologies. I think one key enabler is artificial intelligence and ‘smart bioreactors’ (not sure that even exist today). The other challenge I see is related to the technologies employed to make products out of alternative proteins that are generally less functional in one aspect or the other. There is sometimes an inordinate over-reliance on some ingredients like methylcellulose and I don’t know whether we shouldn’t ask how we can disrupt that ‘glue’. With it is the challenge of a long list of additives that are used to ‘simulate’ meat, for example. Maybe the alt protein enthusiasts ought to admit that giving up animal proteins comes with a loss of some attribute that must not be over-engineered using an endless list of other ingredients. I insist we should think of how to move to ‘clean label’ for alt protein products.

We saw a boom in 2020-2021 in investment into the sector – some crazy figures. We have had a much more challenging year when it comes to attracting finance. What do you make of it all?

I have seen this in the same way I saw ‘crypto craze’. Everybody runs into it until everybody runs out! It is not going to slow down. With today’s ability to invest €50 million here and €100 million there, the glitzy business cases will always find an angel and some enthusiastic crypto-investors. I think the one super-encouraging aspect of financing, at least in Europe, is the deliberate injection of EU grants through respective Member States and regional governments. Governments have been forthcoming with capital incentives and incubator efforts to nurture startups in the alternative proteins space. There will be false starts, failed attempts and some huge winners. I see challenges in the fifth and tenth year as most businesses ought to have broken even. The biggest challenge at the moment is a lot of duplication and startups working on what would look like parts of a bigger puzzle. We should see mergers and/or acquisitions to help stay afloat.

Remaining on the topic of finance, do you think food-tech /alt proteins can weather the storm of the current global economic climate? Or, as they offer a long-term solution to climate change, do you think they will come out the other side relatively unscathed?

At some point alternative proteins shall be ‘proteins’. Just that. If they tarry a little longer, they may be ‘proteins from alternative sources’. The mojo runs out, fatigue in the financial markets, tied up cash from investors and some ‘whales’ muddying the waters. Alternative proteins must move innovations to get incorporated into more food solutions to avoid playing the outsider role. We must move mainstream. And we must do that fast! In terms of money matters, ‘alt protein-friendly’ governments in some countries will guarantee healthy flow of grants, especially with respect to climate change. But that might change. I hope we have not forgotten how hostile a previous US government was to the talk of climate change and the impact of human activities! Having said that, this (money for alt proteins) is way above my punching weight!

What fills you hope about the alt proteins sector – and, conversely, what gets your back up about what you are seeing today?

I am super excited about the ‘adventure’ of the consumers and the concomitant care for our planet. It is inspiring to see that we all care for our appetites (and stomachs) with the same zeal that we care for tomorrow’s generation. We hope that as technology solves our pressure for quality proteins and sustainable nutrients, the cost of those products shall become increasingly affordable. I am also excited that the start-up culture is not restricted to computing. The most irritating thing about the sector is the slow pace in the evolution of the regulators to catch up with the adventures of innovators. We need disruption in regulation as well. Now I get the feeling that regulatory space is dominated by redundant and reactionary mindsets rather than pioneers who are in sync with the immense talent pool of innovators.

What we love about you particularly Seronei is your positivity. So, tell us you hopes and dreams for the industry? And where do you see Sinonin Biotech fitting in to this future?

My hope is that #AltProteins shall cease to be so labeled as such over time as they become mainstream and gain respectable marketshare. We are probably going to see #ProteinsFromAlternativeSources as a trend soon. I see Sinonin Biotech playing in the two main domains: protein innovations and palatability. The growth in alternative technologies used to produce proteins invites partnerships to valorize and upcycle potential waste sidestreams for protein recovery or flavor/palatant development. I expect to see more growths in palatability solutions from ‘animal-free’ proteins and we are well positioned to provide expert knowledge to drive innovations in the respective categories, human and pet food.